I’ve weighed in on numerous occasions, in this column and in my WholeNote album reviews and blogs, about the vast scope of world music as a topic: its misty origins; the limits and problems associated with continued use of what was originally an academic idea, and then became a marketing term. It’s a notion that’s so hard to pin down with any precision, that some would argue not to bother.

Undaunted, I’ve endeavoured to chart its multifaceted presence at key regional venues and among presenters such as the Music Gallery, Small World Music, Royal Conservatory’s Koerner Hall and at the Lula Music and Arts Centre, as performed by its practitioners, and enjoyed – some might use the word consumed – by its myriad audiences. On a couple of occasions I have highlighted stories about its educational role at our regional institutions of higher learning. For instance, my column in the April 2014 issue of The WholeNote featured the flourishing Balinese Gamelan ensemble course offered at Conrad Grebel University College at the University of Waterloo.

For some mysterious reason, perhaps Freudian or Jungian, however, I have so far neglected to explore world music’s abiding 47-year presence at my alma mater, York University’s Music Department. Luckily this March arms me with several reasons to fill that lacuna: ten back-to-back upcoming concerts; two recent conversations; and the retirement of one of York’s key world music animators, Trichy Sankaran.

The first conversation: I turned first to world music's prime initiator at York, the man with the plan, York U. professor emeritus R. Sterling Beckwith. He’s the person I credit with introducing world music ensembles in Canadian universities as continuing credit courses. As York U. Music Department’s founding chair surely he could shed light on its fundamentals. He didn’t disappoint; his trenchant views and passion on the topic were as keen as ever.

The first conversation: I turned first to world music's prime initiator at York, the man with the plan, York U. professor emeritus R. Sterling Beckwith. He’s the person I credit with introducing world music ensembles in Canadian universities as continuing credit courses. As York U. Music Department’s founding chair surely he could shed light on its fundamentals. He didn’t disappoint; his trenchant views and passion on the topic were as keen as ever.

“World music along with jazz has now been taken up by many American and Canadian universities; they have become fixtures there,” he began. “Long gone are the days when they considered it beneath their interest,” he added.

“Well before I arrived at York, I took [pioneering] ethnomusicologist Mantle Hood’s Javanese gamelan class at Harvard. I also spent time with the retired senior musicologist Charles Seeger. Among other things, he praised the American Carnatic singer and ethnomusicologist Jon Higgins whose bi-musical [a term coined by ethnomusicologist Mantle Hood] reputation preceded him.” Even though Higgins was still at the very start of a remarkable career, he had already concertized, broadcast and recorded a Carnatic music LP with renowned musicians in India. (Spoiler alert: Higgins became a teacher and a mentor of mine at York.)

There is a back story here which Beckwith helpfully sketched for me. Mantle Hood’s groundbreaking ethnomusicology program at UCLA, established in 1960, came complete with performing ensembles, and produced Robert Brown the person who in turn kick-started the World Music program at Wesleyan University. Through Brown, we can trace the teacher-student lineage to Higgins. Brown served as Higgins’ PhD thesis advisor at Wesleyan. “I consider other American university ethnomusicology programs such as those at Washington University also direct descendants of Hood’s groundbreaking efforts at UCLA,” Beckwith added.

“Yet another defining pre-York U. experience was the discussion I had with the late Ravi Shankar about introducing applied Indian music studies at York. He was intrigued and recommended his sitar disciple Shambhu Das, who as it turned out, was already living in Toronto. All of that was in my head when I arrived here in 1969.”

Beckwith continued, “I was determined to implement the paradigm-altering gamelan experiences I had with Hood and the inspiring conversations I had with Seeger, as well as doing what I could to bring Higgins to York. As events would have it, my last official act as Music Department chair was to be able to hire Jon Higgins, which made it possible in turn to hire the gifted percussionist Trichy Sankaran a little later.”

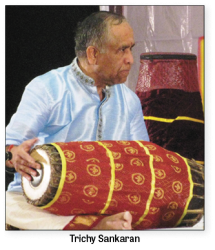

Trichy Sankaran: One of Beckwith’s first world music hires, in 1971 – and significantly also one of the longest serving – was a mridangam and kanjira player with an international career, Trichy Sankaran. Sankaran passed a significant milestone last fall, retiring from York in September 2015 after an illustrious career spanning 44 years as a professor of music, researcher and textbook author. As well as serving as a co-founding director of its Indian music studies, one of Canada’s first university-based world music performance programs, he also developed hybrid Carnatic and Western pedagogical practices. Certainly one of Sankaran’s most significant contributions at York was his marked influence on a couple of generations of students, many of whom have gone on to become established musicians, composers and educators. His outstanding achievements as an educator were recognized with the OCUFA Award, given by the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations for teaching excellence.

Trichy Sankaran: One of Beckwith’s first world music hires, in 1971 – and significantly also one of the longest serving – was a mridangam and kanjira player with an international career, Trichy Sankaran. Sankaran passed a significant milestone last fall, retiring from York in September 2015 after an illustrious career spanning 44 years as a professor of music, researcher and textbook author. As well as serving as a co-founding director of its Indian music studies, one of Canada’s first university-based world music performance programs, he also developed hybrid Carnatic and Western pedagogical practices. Certainly one of Sankaran’s most significant contributions at York was his marked influence on a couple of generations of students, many of whom have gone on to become established musicians, composers and educators. His outstanding achievements as an educator were recognized with the OCUFA Award, given by the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations for teaching excellence.

Along with Beckwith, I and many other Sankaran friends, colleagues and students were present at York’s Tribute Communities Recital Hall last September. Few there doubted that the event marked the closing of a long and important first chapter in the music department’s grand – and continuing – adventure in world music education.

The occasion was celebrated in style with a formal concert in which Sankaran was joined on stage by his vocalist daughter Suba Sankaran, leader of the JUNO-nominated Indo-jazz-funk fusion ensemble Autorickshaw, and her bandmates, bass guitarist and singer Dylan Bell, and tabla player Ed Hanley. The musicians gave authoritative performances of solo and ensemble works, the repertoire including original compositions by the senior Sankaran. As well as signalling the passing on of an intergenerational musical torch, it additionally asserted (at least my awareness of) the emergence of a specific family-centered kind of Indo-Canadian hybrid music-making, echoing the venerable Indian tradition of guru-shishya parampara. As for the continuity of Carnatic music education at York pioneered by Sankaran, that subject appears to be moot.

The second conversation: Throughout its first three decades, York’s world music ensemble courses remained relatively constant and few. It was only around the very early 2000s that I became aware of a dramatic increase in the number of world music ensembles. The trend only crossed my personal radar after, in 1999, I was hired, by Michael Coughlan, the incoming Music Department chair, as the founding course director of the Javanese Gamelan (ensemble) course. During the years I taught the course, the number and range of music ensembles seemed to grow almost exponentially, and the students attracted to them likewise swelled.

What’s the current state of the university’s world music ensemble program? I spoke to the ethnomusicologist, singer and instrumentalist Irene Markoff, whose research and performing activities centre on the musical traditions of Bulgaria, Turkey and the Balkans. “I began to teach there in 2001,” she told me. “At one point I taught global musicianship to music majors. Placed in the context of performance rather than listening to recorded musical examples, my approach was well received by the students.” Her ensemble courses however also include non-music major students. Markoff gave an example, “I currently have a number of students of Chinese heritage in my ensemble who can sing complex metrical parts, despite being non-music majors. They sometimes outstrip music majors in mastering some of these [perceived difficult] performing skills.”

While generally bullish on York’s music course offerings, she did express a wish: “That our music students would be required to take a world music ensemble.” Why? “For the simple reason that we live in a multicultural society and I believe such study will broaden students’ musical horizons. Also with musical hybridities [being a regular fact of musicians’ lives today], it’s important for learners to be exposed to the broad spectrum of metres, multi-part singing styles and tonal modes,” all benefits afforded by learning music outside of the Western mainstream.

I asked Markoff about the future of the world music ensembles. “I have proposed the production of ensemble music videos hosted on the department’s website as a means of attracting future students. As for their relevance, I believe these ensemble courses will continue to well serve music students, exposing them to ‘other’ musical practices and to increase their appreciation and understanding of peoples.”

In a nutshell, Markoff believes such educational ensembles, which allow students to experience the musical diversity of cultures, tend to “build bridges rather than erecting walls between cultures.”

York University’s World Music Festival runs March 17, 18 and 21 at various venues, all in the Accolade East Building.

Mar 17 the World Music Festival kicks off with the Cuban Ensemble conducted by Rick Lazar and Anthony Michell, followed by West African Drumming, Ghana, led by Kwasi Dunyo. That afternoon Lazar’s Escola de Samba rules the Sterling Beckwith Studio, followed by West African Mande, Anna Melnikoff, conductor.

Mar 18 Irene Markoff conducts the Balkan Music Ensemble at 7:30pm at the Tribute Communities Recital Hall. Earlier that day performances by the Celtic Ensemble conducted by Sherry Johnson, Chinese Classical Orchestra directed by Kim Chow-Morris, Caribbean Ensemble conducted by Lindy Burgess and Charles Hong’s Korean Drum Ensemble will echo in various Accolade East Building halls.

It’s a World Music Festival wrap Mar 21 with the World Music Chorus conducted by Judith Cohen, a course I greatly enjoyed a few years ago when I returned (yet again!) to my music studies at York. Please consult The WholeNote listings for times and venue details.

University of Toronto Faculty of Music: York University is certainly not the only world music game in town. Apr 7 the U of T Faculty of Music presents its World Music Ensembles in concert at Walter Hall. Featured are the African Drumming and Dancing Ensemble, Latin-American Percussion Ensemble and Steel Pan Ensemble. I’ve been attending these concerts since their inception and have never failed to be inspired by the enthusiasm and musical skill demonstrated.

Quick Picks

Mar 2 the COC’s noon-hour World Music Series presents Avataar. Directed by saxophonist and composer Sundar Viswanathan the all-star Toronto group often includes Michael Occhipinti (guitar), Justin Gray (bass), Felicity Williams (voice), Ravi Naimpally (tabla) and Giampaolo Scatozza (drum set). They’ll be playing selections from their recently released album Petal. Arrive early.

BRASH: It is just the sort of weather, however unseasonable, for “BRASH! A Badass Brass Festival,” presented by Lemon Bucket Orkestra (LBO) and Small World Music, on Mar 11 and 12 at the Opera House on Queen St. E. LBO with its high hipster street cred needs no further introduction in these pages. Ratcheting up the badass quotient a notch will be Toronto’s Rambunctious and Montreal’s Gypsy Kumbia Brass Band.

Mar 11, 12 and 13 at the Betty Oliphant Theatre the Raging Asian Women (RAW) Taiko Drummers perform an evening of stories from the drummers’ lives, in collaboration with Asian Canadian performers Teiya Kasahara (voice) and Heidi Chan (percussion and flute). "Crooked Lines: Stories in Between" involves video vignettes along with the taiko drummers' trademark ferocity and spirit.

Mar 26 the Small World Music Centre presents a smaller, more intimate and reflective musical experience, though in no way any less passionate: the Dilan Ensemble directed by Shahriyar Jamshidi, a kamancheh (bowed lute) player, composer and vocalist, now settled in Canada. "In the Shadow of the Fatherland" is a cross section of the repertoire the Iranian Kurdistan native has devoted his career to preserving and transmitting. Jamshidi is joined by local cellist Raphael Weinroth-Brown.

Apr 2 and 3 The Aga Khan Museum continues its impressively inclusive concert programming, partnering with the venerable presenter Raag-Mala Music Society of Toronto in two concerts titled Raags of the Gharana Tradition. Apr 2, Maihar gharana (musical school, lineage) sitarist Anupama Bhagwat and Agra gharana singer Waseem Ahmed Khan render a selected few of the vast set of Hindustani evening raags. Apr 3 at 3pm it’s time for a much rarer section of afternoon raags; many “classical” ragas/raags are associated with four three-hour timeframes and for maximum effect are performed at those prescribed times. Sarangi player Ramesh Mishra, a disciple of Ravi Shankar (of the Maihar gharana), shares the concert with the vocalist Devaki Pandit who has studied with gurus of both Jaipur and Agra gharanas.

Also on Apr 2 Nagata Shachu, with Kiyoshi Nagata as its music director, joins one of the city’s leading percussion ensembles TorQ in concert at the Brigantine Room, Harbourfront Centre. Expect an engaging, polished Japanese, Western and world percussion music mix.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.