Still Singing Britten’s Praises

No one should ever need an excuse to attend a concert of the music of iconic English composer Benjamin Britten. But if modern music remains something you consider forbidding or unpleasant, find a reason to hear some Britten — experiencing some of his music live could be an enjoyable way to forge a new perspective. This is the centenary year of Britten’s birth and there will be many opportunities to hear his works. This year’s focus on modern music in the Choral Scene column gives me a chance to devote some space to this important composer.

Celebrated from an early age, Britten enjoyed both respect from his colleagues and a rare level of public popularity throughout his career. His first opera, Peter Grimes, was an international hit in 1945. He continued to compose operas throughout his career, but also wrote forall manner of choirs, ensembles and solo instrumentalists.

Celebrated from an early age, Britten enjoyed both respect from his colleagues and a rare level of public popularity throughout his career. His first opera, Peter Grimes, was an international hit in 1945. He continued to compose operas throughout his career, but also wrote forall manner of choirs, ensembles and solo instrumentalists.

Britten founded his own music festival in 1948 — The Aldeburgh Festival — and maintained a profitable relationship with Decca Records that ensured that his works would be recorded almost as soon as they were produced. The stereotypical model of the 20th century modernist composer — a writer of unpleasant and inaccessible music, ignored by and scornful of the crowd — is not one that Britten ever believed in or embodied.

Of course, only in the museum-like culture of classical music would a composer who was born a century ago and died in 1976 even be considered modern. Surely for those who are interested in new sounds, other composers have gone farther since. Why bother with Britten?

I’d argue that like Beethoven and Mozart, Britten’s music appeals on many different levels. His ability to draw on and interpret elements of popular music, folk song and baroque music (notably that of Purcell, whose work Britten helped revive) has always attracted listeners who like strong tunes and lively rhythms.

But his individual voice and singular musical outlook moulded and developed these popular elements in unique ways. He was no musical conservative, playing it safe with conventional sounds. His work often took melodies and obvious chord changes and nudged the musical language sideways into areas that no one could anticipate or expect. A lot of mid-century music that is more simplistic – or more experimental — has dated more obviously than the best of Britten’s work.

While Britten will likely be most remembered for his operas — which contain stunning choral sections, notably in Peter Grimes, Billy Budd and Death in Venice — his music also furthered the English cathedral choral tradition.

English choral music of the Renaissance and early Baroque was brilliant and accomplished, but then languished in the decades that followed until the end of the 19th century, when it was revitalized by the the work of composers such as Holst, Elgar and Vaughan Williams. Britten further enlivened this tradition in the 20th century with oratorios and anthems that balanced immediate appeal with inventiveness and innovation. Several concerts take place in the coming weeks that will give choral audiences a chance to hear some of these compositions.

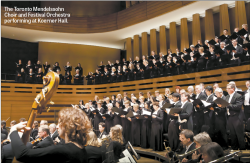

Toronto Mendelssohn Choir performs a Britten double bill November 20, with his Saint Nicolas (1948) and The Company of Heaven (1937). Saint Nicolas, of course, is the fourth-century Greek bishop and saint whose legendary exploits form the basis for the modern Santa Claus. But Britten’s cantata is thankfully free of any kind of cutesiness or sentimentality, and instead presents a portrait of Nicolas as vulnerable, dynamic and conflicted.

Because the cantata was written to be performed in part by schoolchildren, the music is also both mischievous and exuberant, especially in the choral sections. St Nicolas has wonderful moments — an exciting musical depiction of a storm at sea which Nicholas calms with prayer (“He Journeys to Palestine”), and a grisly but entertaining sequence in which children eaten by starving villagers are brought back to life (“The Pickled Boys”).

This work is great fun for children and youth to perform and attend, especially when staged. It really ought to be a Christmas perennial, a familiar favourite on the level of other choral works regularly performed at that time of year.

Unfortunately, a performance of St. Nicolas is relatively rare, and a performance of his 1937 The Company of Heaven is even rarer. I have never actually heard this piece live, and am looking forward to attending this concert. The theme of the cantata is of angels — the “company of heaven” — and their metaphysical battle with evil. Britten assembled poetry on this theme from diverse sources ranging from the Bible to Christina Rossetti and William Blake. Some of the poetry is set to music, some is recited. Britten combines his own music with a setting of the hymn “Ye watchers and ye holy ones,” a standard of the Anglican tradition, and one that would have had deep resonance for a nation on the edge of war.

Orpheus: Another opportunity to hear Britten comes courtesy of the Orpheus Choir of Toronto, which performs his 1938 cantata World of the Spirit on November 5. Britten was a life-long pacifist whose loathing of cruelty, especially involving children, is a theme that recurs in many of his compositions. Britten lived briefly in America during the beginning of WWII, in part because his pacifist leanings were not well received in pre-war Britain. World of the Spirit, a piece that draws on varied texts that express love, hope and tolerance, is both manifesto and plea. This performance is the Canadian premiere of this rare work, so attending the concert is a chance to take part in a bit of Britten’s own ongoing history.

This concert also features a very special event. John Freund, a great lover and supporter of music in Toronto, is also a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps Terezin and Auschwitz. He will read from his memoir I Was One of the Lucky Few: The Story of My Childhood. The readings will be interspersed with choral music and visual imagery, in the kind of multimedia presentation that has become an Orpheus Choir specialty.

I hope I’ve persuaded those unfamiliar with Britten to consider having a listen at some point this year. But I’m conscious that I’ve neglected other groups in doing so, especially since the number of choral concerts taking place increases exponentially as the end of the calendar year approaches. Here are “quick pick” listings for some of the other choral offerings available this month — there is some very inventive programming taking place.

Quick Picks

All the following are well worth checking out in the listings.

All the following are well worth checking out in the listings.

Nov 2, 7:30: Chorus Niagara. Handel: Grand and Glorious. Beyond GTA.

Nov 2, 8:00: Renaissance Singers. Psalms of David. Beyond GTA.

Nov 9, 8:00: DaCapo Chamber Choir. Evening Song. Beyond GTA.

Nov 9, 8:00: Guelph Chamber Choir. Passion of Joan of Arc

(Carl Dreyer’s 1928 silent film with live music). Beyond GTA.

Nov 9, 7:30: Amadeus Choir. The Writer’s War: A Tribute to War Correspondents.

Nov 13, 7:30: St. James Cathedral. Mozart’s Requiem.

Nov 16, 7:00: Church of the Ascension. Toronto Mass Choir.

Nov 22, 7:30: Georgetown Bach Chorale and Baroque Soloists.

Bach: Christmas Oratorio Part One and Magnificat.

Nov 23, 7:30: Cantemus Singers. Sing Noel!

Nov 23, 7:30: Jubilate Singers. This Shining Night.

Nov 23, 8:00: Bell’Arte Singers. Of Remembrance and Hope.

Nov 27, 7:30: Toronto Children’s Chorus. Take Flight.

Ben Stein is a Toronto tenor and theorbist. He can be

contacted at choralscene@thewholenote.com.

Visit his website at benjaminstein.ca.photo for choral quick picks.