The New York Philharmonic: From Bernstein to Maazel by John Canarina

The New York Philharmonic: From Bernstein to Maazel

The New York Philharmonic: From Bernstein to Maazel

by John Canarina

Amadeus Press

495 pages, photos; $29.99 US

• In this engaging history of the New York Philharmonic, John Canarina relates how someone at a public forum in 1991 suggested that the orchestra should install a giant mirror at the rear of the stage so audiences could watch the conductor’s facial expressions. The orchestra’s music director at the time, Kurt Masur, responded, “When I conduct Beethoven, I wouldn’t like to replace Beethoven. He should be in your mind, not me.” Masur’s attitude is similar to that of another of the orchestra’s long-time conductors, Leonard Bernstein. In fact, the orchestra has consistently attracted principal conductors who, like Masur and Bernstein, are more concerned with letting the composers’ voices be heard than stamping their own personalities on the orchestra. This has allowed the distinctive sound of the orchestra – which Canarina characterizes by its openness and immediacy – to develop under a succession of conductors.

Canarina, who was an assistant conductor with the orchestra under Leonard Bernstein, starts his history with Bernstein, who took over from Dmitri Mitropoulos in 1958 amid concerns that he was just a “personality boy.” At 39 he was considered too young to lead a major orchestra, though today that doesn’t sound so young, with 29-year-old Gustavo Dudamel leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic and 35-year-old Canadian Yannick Nézet-Séguin leading both the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Rotterdam Philharmonic. In any case, the choice of Pierre Boulez sparked even more controversy, though it turned out to be just as visionary.

The conductors are quite properly Canarina’s main focus. But he certainly gives the orchestra players their due. He quotes his own interviews with orchestra members and highlights the work of legendary principal players like cellist Lorne Munroe, flutist Jeanne Baxtresser, (who came to the orchestra from the Toronto Symphony), clarinettist Stanley Drucker, and current concertmaster Glenn Dicterow.

Canarina also pursues his particular interest in how the orchestra has been treated by the press throughout the years, which leads to numerous quotations from past reviews. But far more interesting are the quotes from performers, composers and conductors, and especially his own insightful comments, which enhance this lively portrait of a great orchestra.

A Biographical Guide to the Great Jazz and Pop Singers

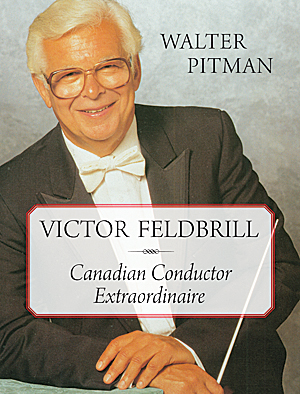

A Biographical Guide to the Great Jazz and Pop Singers Victor Feldbrill: Canadian Conductor Extraordinaire

Victor Feldbrill: Canadian Conductor Extraordinaire Listen to This

Listen to This