Let’s call it a personal rite of spring. Along with those first warm sunny days, I also look forward to engaging with the larger world in concerts at several of our region’s universities and concert halls.

Let’s call it a personal rite of spring. Along with those first warm sunny days, I also look forward to engaging with the larger world in concerts at several of our region’s universities and concert halls.

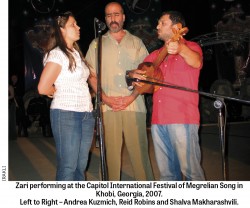

This season, my first focus falls on Toronto’s award-winning vocal and instrumental trio Zari, which performs April 25 at the little jewel of downtown venues, Musideum. Composed of Shalva Makharashvili, Andrea Kuzmich and Reid Robins, Zari (meaning “bell” in Georgian) draws on the rich regional repertoire of the polyphonic songs of the Republic of Georgia. Standing at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, their ancient country is called Sakartvelo by Georgians.

Declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2001, Georgian vocal polyphony, with its close harmonies and untempered scales, is characterized by three-part singing in a variety of regional styles. The songs range from the haunting melismatic melodies of the Eastern provinces, to the wild, explosive counterpoint of the West. They also include more recent romantic urban ballads.

Like many other groups I’ve highlighted in this column who have musical affiliations to another part of the world, Zari was made in Toronto. I spoke with the singer, ethnomusicologist and group co-founder Andrea Kuzmich to get the skinny on Zari.

“It was formed in 2003. We met each other a few years earlier at the downtown Toronto living room singing sessions of Darbazi” (Canada’s first Georgian choir). Kuzmich quickly identified a key feature of the group, its dedication to studying the older strata of Georgian music in its birthplace. “We want to deepen our understanding of and feeling for this musical treasure. When Zari performs, we embrace the profundity of Georgian culture: its roots embedded in ancient times, its strength and courage to survive and its inspiring hospitality.” To that end the trio plans to return to Georgia this October for another round of studies and concerts.

And like numerous Canadian groups that reference other geo-cultural milieus, Zari is perhaps better known there than here. Kuzmich notes that during past Georgian tours, “we have performed at the Chveneburebi festival, Festival of Megrelian song, First International Festival of Gurian Song and other festivals that have taken us around the country.” They have also been featured at the “best performance halls of [the capital] Tbilisi, such as the Opera House, and the Philharmonia Concert Hall.”

In addition to formal concert venues, Kuzmich points out the hard-to-overstate significance of the supra. It’s the traditional, often epic, Georgian feast which serves as an important locus for Georgian social culture – and singing. “You know ... there’s a saying that the best performances happen at the supras after the concerts. We can’t really predict how many supras we’ll attend or which ones will be most educational.” And the supra is such an integral part of Georgian culture that it’s not easy to separate the supra from what happens each day. “There will be [formal] toasting every day, if not multiple times in the day, perhaps even around a table while we’re learning a song. In that case the line between supra and lesson gets blurred.”

She gives an example of how such productive blurring can evolve. “[One day] we were all set to have a lesson, but instead had an impromptu midday supra at a small local house-restaurant in Makvaneti, the village of our Gurian [region of Georgia] teachers …. At the supra they sang many songs, interlaced with stories about music-making from when they were little boys, during Soviet times, and today. We sang with them too, sometimes trading off at inner cadence points. We probably sat there for over three hours. All three of us [in Zari] felt inspired and very connected to the tradition [after that experience], and we learned so much in that one sitting.”

I asked about Zari’s Musideum set list. “We’ll be performing songs from several regions of the country,” said Kuzmich. She mentioned a few songs on their long list. One of the Gurian songs is Chven Mshvidoba (Peace to Us). “We are in the process of learning a fourth or fifth variant, though in performance we tend to just let the improvisation happen.” Maglonia, a lyrical song from Samegrelo, features accompaniment by the panduri, a prominent Georgian three-string lute. “There are a few versions we are listening to, but the one we mostly base our version on is by Polikarpe Khubulava, the Georgian master singer who passed away on January 1, 2015,” she added. “We will also do songs from [the regions of] Imereti and Achara, which are similar, though Imereti has more parallel thirds in the top voice, plus one of those dense Svaneti chordal songs. It’s a place which is snowbound for eight months of the year and the songs, like the people, are rugged.”

Zari feels the need to regularly re-connect with those wellsprings of the oral musical tradition they’ve been born into – or as in the case of Kuzmich, chosen – in order to fuel their inspiration and artistry. Their Musideum concert is part of a series of fundraisers to help get them back to Georgia to study with elder master singers, some well past retirement age. In addition to such venerable living connections to the past, the trio also plans to re-connect with researchers at the Conservatoire, including colleagues at the Ethnomusicology Department and the Research Centre for Traditional Polyphony. “Giorgi Donadze, the leader of Basiani [a prominent choir], is also the director of the State Folk Centre, so we’ll be connecting with that institute,” adds Kuzmich. “And we always try to meet up with Anzor Erkomaishvili, who endows us with new publications on Georgian music.”

It’s always exciting to hear such a depth of passion and engagement from an artist. I plan to catch Zari’s Musideum show to hear the latest in the evolution of Georgian music, Toronto style.

World music in the university: April 1 the University of Toronto Faculty of Music holds its annual spring concert of World Music Ensembles at Walter Hall, Edward Johnson Building. This season it’s the African Drumming and Dancing, Latin American Percussion and Steel Pan student groups’ turn to shine. Kwasi Dunyo, the Ewe master drummer from Ghana who has for two decades been teaching in universities and schools in Canada and the U.S.A. from his Toronto home base, leads the first ensemble. The Latin American percussion group is led by the accomplished Mark Duggan, an orchestral percussionist, composer and jazz musician. Even 32 years ago his highly honed skills were in demand: he was chosen to play with Canada’s first gamelan, the Evergreen Club. Michelle Colton, an emerging multi-percussionist and educator, directs the Steel Pan ensemble.

The next day, on April 2 at noon, the world music focus shifts to the Maureen Forrester Recital Hall, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, where the Conrad Grebel Gamelan Ensemble performs, directed by Maisie Sum. Introduced into the university as a course only two years ago by Sum, the gamelan semara dana, a kind of Balinese tuned percussion-rich instrumental ensemble, is the first of its kind in Southwestern Ontario. In an interview with The WholeNote a year ago professor Sum reported an enthusiastic reception for the music among the students. “Enrollment for the ensemble doubled in the winter term, so we currently have two groups.”

After the excitement of the noon-hour Waterloo Balinese set, there’s still plenty of time to get down to St. Catharines’ Brock University the same day for an evening concert. Jaffa Road performs at the Sean O’Sullivan Theatre, Centre for the Arts. The JUNO short-listed Toronto world music group offers an amalgam of sacred and secular Jewish song, jazz, Indian and Arabic music, with touches of electronica and dub.

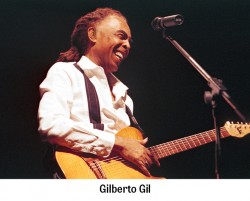

Brazil’s musical ambassador: April 7 the Royal Conservatory of Music presents “Gilberto Gil: Gilberto’s Samba” at Koerner Hall. Hailed as “Brazil’s musical ambassador,” for more than 40 years the singer, composer, guitar player – and former Minister of Culture – has enjoyed an extraordinary career. Gil is perhaps best known as an eloquent exponent of bossa nova, but he is also a pioneer of the tropicalia and Brasileira genres. The New York Times summed up his monumental yet affable stage presence: “delicate bossa novas, strummed rockers and intricate sambas … Mr. Gil didn’t trumpet his virtuosity. It was offered genially, like his melodies and his un-didactic thoughts on love, poetic license and mortality.”

Brazil’s musical ambassador: April 7 the Royal Conservatory of Music presents “Gilberto Gil: Gilberto’s Samba” at Koerner Hall. Hailed as “Brazil’s musical ambassador,” for more than 40 years the singer, composer, guitar player – and former Minister of Culture – has enjoyed an extraordinary career. Gil is perhaps best known as an eloquent exponent of bossa nova, but he is also a pioneer of the tropicalia and Brasileira genres. The New York Times summed up his monumental yet affable stage presence: “delicate bossa novas, strummed rockers and intricate sambas … Mr. Gil didn’t trumpet his virtuosity. It was offered genially, like his melodies and his un-didactic thoughts on love, poetic license and mortality.”

Taiko meets tabla: April 11 two established groups on the Toronto world music scene join for an evening of transcultural percussion-centric musical dialogues. The Japanese taiko group Nagata Shachu directed by Kiyoshi Nagata meets the JUNO-nominated Toronto Tabla Ensemble directed by Ritesh Das on the stage of the Brigantine Room, Harbourfront Centre. Having attended concerts by both groups from their early days, it’s evident that collaborations are important to each. Nagata shares that “I feel that the primal and thunderous sounds of the taiko are a perfect complement to the subtle and intricate rhythms of the tabla. Ritesh and I feel a certain connection, both musically and in terms of how we were trained in our respective traditions.” The personal history the two directors share is an important link between their groups. “I am thrilled to be once again working with Kiyoshi Nagata,” reflects Das. “[He was] one of the first artists I collaborated with after coming to Toronto in 1987. When we rehearsed for the first time in 20 years, I felt a new sense of maturity from both ends, which led to an immediate understanding between us. Together we can create a very rich and elegant Indo-Japanese collaboration.” This respectful fusion not only marks an advanced musical maturity, but is a positive thermometer of the future health of Toronto’s world music scene.

At the Aga Khan Museum: A week later the new Aga Khan Museum and the well-established Raag-Mala Music Society of Toronto join forces for the first time in two concerts at the Aga Khan Museum Auditorium. Titled “Miyan-Ki-Daane: Raags of Tansen,” the programs, presented in the Hindustani dhrupad and khayal music genres, celebrate the music of Miyan Tansen, a bright star among the composers and singers of Emperor Akbar’s 16th-century North Indian court. His beautiful compositions have been passed on through many generations of oral tradition through the guru-shishya parampara, the particular manner of transmission from teacher to disciple in traditional Indian culture.

The first program April 18 features singer Samrat Pandit and bansuri (bamboo flute) player Rupak Kulkarni. The singer received the prestigious Sangeeta Shiromani Award from the State of Maharashtra just last year, while Kulkarni is widely recognized as a leading bansuri player. On April 19 Uday Bhawalkar, among the foremost exponents of dhrupad singing today, and the respected sitarist Partha Bose, present an unusual 11am late morning concert. Audiences will thus have a rare opportunity to hear raags appropriate to that time of day, a practice still maintained in Hindustani classical music. It’s definitely worth making alternate work arrangements for this concert.

April 24, also at the Aga Khan Museum, sounds of the Sahara, the Magreb and West Africa are blended with contemporary pop and funk by the powerhouse Noura Mint Seymali. This compelling singer, a star in Mauritania, was born into a prominent Moorish griot family. She is also a master of the ardine (nine-stringed harp) and a composer.

Andrew Timar is a Toronto musician and music writer. He can be contacted at worldmusic@thewholenote.com.