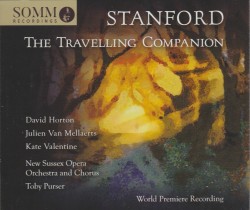

Charles Villiers Stanford: The Travelling Companion - Horton; Mellaerts; Valentine; New Sussex Opera Orchestra and Chorus; Toby Purser

Charles Villiers Stanford – The Travelling Companion

Charles Villiers Stanford – The Travelling Companion

Horton; Mellaerts; Valentine; New Sussex Opera Orchestra and Chorus; Toby Purser

Somm Recordings SOMMCD 274-2 (naxosdirect.com)

In 1835 Hans Christian Andersen published The Travelling Companion, a touching yet violent story full of wizards, princesses and mysterious strangers; in 1916, the Irish composer Charles Villiers Stanford set this text to music, creating what would be his last opera. Although reprised occasionally since its premiere, this recording of The Travelling Companion is the first of its kind, captured live at Saffron Hall in December 2018.

It is immediately noticeable that this is a live recording, as the sound quality lacks some clarity, with slightly blurred timbres and occasionally opaque orchestrations, as well as the feeling that everything is being performed at a distance. Despite the issues of transferring this live performance to disc, the musical execution itself is of notably high quality, with soloists, chorus and orchestra combining to present a cheerful and charming interpretation.

Cheerful and charming are also the best words to describe Stanford’s score, which maintains the levity and brevity characteristic of early-20th-century English music, never falling into verismo’s dramatic angst or Wagnerian mysticism. Major keys run consistently throughout the work, as do little woodwind marches, fanfares, and lighthearted figurations. This can only be taken as a deliberate decision on the part of Stanford, for his symphonic and choral works are some of the most stunning of his era and leave no doubt that this was a man who was highly capable of writing whatever music he wished to hear.

English opera has relatively few major composers to its credit: Purcell, Handel and Britten are three that have maintained a presence in modern opera houses, but there are also works which are only occasionally revived and recorded that are well worth listening to. Such is the case with Stanford’s The Travelling Companion and this disc by New Sussex Opera.