Since at least after World War Two, the skill of Japanese players of every type of music has been unquestioned, and it’s the same for jazz and improvised music. However since non-notated music’s bias has been North American and European-centred, except for the few who moved to the US, numerous Japanese innovators are unknown outside the islands. But these discs provide an overview of important players’ sounds and the evolution of the form.

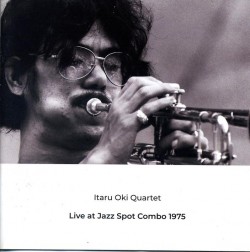

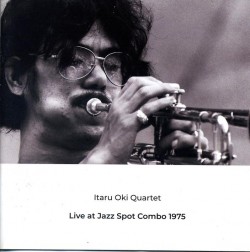

Although arriving from a dissimilar tradition, free-form experiments were common in 1960s Japan with several avant-garde ensembles throughout the country. One player who tried for more international renown was trumpeter Itaru Oki (1941-2020). He relocated to France in 1974 and was soon playing with locals. Occasionally he returned to gig in Japan, and Live at Jazz Spot Combo 1975 (NoBusiness NBCD 143 nobusinessrecords.com) reproduces one of those visits. Playing with drummer Hozumi Tanaka who was part of his Japanese trio, bassist Keiki Midorikawa and, crucially, alto saxophonist/flutist Yoshiaki Fujikawa, Oki’s quartet roams through five themes and improvisations. The trumpeter’s truculent flutters set the pace with speedy arabesques in counterpoint to slithery flute flutters. While keeping the exposition horizontal, the trumpeter prolongs intensity with triplets and half-valve effects. Backed by sul tasto bass string rubs and percussion slaps, Fujikawa is even more assertive beginning with Combo Session 2, where initial saxophone concordance with trumpet puffs soon dissolves into strangled reed cries and irregular vibrations. Dragging an emotional response from Oki, both horns are soon exfoliating the narrative, seconded by cymbal shivers. But the four stay rooted enough in jazz to recap the head after cycling through theme variations. These opposing strategies are refined throughout the rest of this live set. But no matter how often the saxophonist expresses extended techniques such as doits and spetrofluctuation, linear expression prevents aural discomfort. In fact, the concluding Combo Session 5 could be termed a free jazz ballad. While Oki’s tonal delineation includes higher pitches and more note expansion than a standard exposition, at points he appears to be channelling You Don’t Know What Love Is. That is, until Midorikawa’s power pumps, Tanaka’s clapping ruffs and the saxophonist’s stentorian whistles and snarls turn brass output to plunger emphasis leading to a stimulating rhythmic interlude. With trumpet flutters descending and reed trills ascending a unison climax is reached.

Although arriving from a dissimilar tradition, free-form experiments were common in 1960s Japan with several avant-garde ensembles throughout the country. One player who tried for more international renown was trumpeter Itaru Oki (1941-2020). He relocated to France in 1974 and was soon playing with locals. Occasionally he returned to gig in Japan, and Live at Jazz Spot Combo 1975 (NoBusiness NBCD 143 nobusinessrecords.com) reproduces one of those visits. Playing with drummer Hozumi Tanaka who was part of his Japanese trio, bassist Keiki Midorikawa and, crucially, alto saxophonist/flutist Yoshiaki Fujikawa, Oki’s quartet roams through five themes and improvisations. The trumpeter’s truculent flutters set the pace with speedy arabesques in counterpoint to slithery flute flutters. While keeping the exposition horizontal, the trumpeter prolongs intensity with triplets and half-valve effects. Backed by sul tasto bass string rubs and percussion slaps, Fujikawa is even more assertive beginning with Combo Session 2, where initial saxophone concordance with trumpet puffs soon dissolves into strangled reed cries and irregular vibrations. Dragging an emotional response from Oki, both horns are soon exfoliating the narrative, seconded by cymbal shivers. But the four stay rooted enough in jazz to recap the head after cycling through theme variations. These opposing strategies are refined throughout the rest of this live set. But no matter how often the saxophonist expresses extended techniques such as doits and spetrofluctuation, linear expression prevents aural discomfort. In fact, the concluding Combo Session 5 could be termed a free jazz ballad. While Oki’s tonal delineation includes higher pitches and more note expansion than a standard exposition, at points he appears to be channelling You Don’t Know What Love Is. That is, until Midorikawa’s power pumps, Tanaka’s clapping ruffs and the saxophonist’s stentorian whistles and snarls turn brass output to plunger emphasis leading to a stimulating rhythmic interlude. With trumpet flutters descending and reed trills ascending a unison climax is reached.

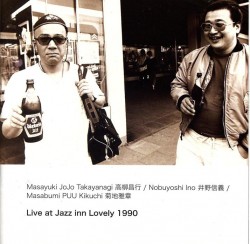

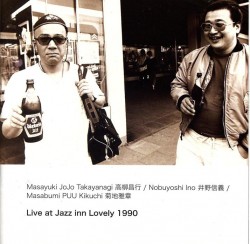

Flash forward 15 years and more instances of first generation Japanese free music are on Live at Jazz Inn Lovely 1990 (NoBusiness NBCD 135 nobusinessrecords.com). In one way it was a reunion between two pioneering improvisers, guitarist Masayuki Jojo Takayanagi (1932-1991), who began mixing noise emphasis and free improvisation in the mid-1960s with in-your-face groups featuring the likes of saxophonist Kaoru Abe and pianist Masabumi Puu Kikuchi (1939-2015). Kikuchi evolved a quieter style after moving to the US in the late 1980s and this was the first time the guitarist and pianist played together since 1972. Problem was that this was a Takayanagi duo gig with longtime bassist Nobuyoshi Ino until Kikuchi decided to sit in, creating some understandable friction. Agitation simmers beneath the surface adding increased tautness to the already astringent sounds. This is especially obvious on the trio selections when the guitarist’s metallic single lines become even chillier and rawer. Initially more reserved, Kikuchi’s playing soon accelerates to percussive comping, then key clangs and clips, especially on the concluding Trio II. For his part, Ino serves as a bemused second to these sound duelists, joining an authoritative walking bass line and subtly advancing swing to that final selection. On the duo tracks, he and the guitarist display extrasensory connectivity. He preserves chromatic motion with buzzing stops or the occasional cello-register arco sweep. Meanwhile with a minimum of notes, Takayanagi expresses singular broken chord motion or with slurred fingers interjects brief quotes from forgotten pop tunes. On Duo II as well, Ino’s string rubs move the theme in one direction while Takayanagi challenges it with a counterclockwise pattern. Still, fascination rests in the piano-guitar challenges with Kikuchi’s keyboard motion arpeggio-rich or sometime almost funky, while Takayanagi’s converse strategies take in fluid twangs, cadenced strumming and angled flanges.

Flash forward 15 years and more instances of first generation Japanese free music are on Live at Jazz Inn Lovely 1990 (NoBusiness NBCD 135 nobusinessrecords.com). In one way it was a reunion between two pioneering improvisers, guitarist Masayuki Jojo Takayanagi (1932-1991), who began mixing noise emphasis and free improvisation in the mid-1960s with in-your-face groups featuring the likes of saxophonist Kaoru Abe and pianist Masabumi Puu Kikuchi (1939-2015). Kikuchi evolved a quieter style after moving to the US in the late 1980s and this was the first time the guitarist and pianist played together since 1972. Problem was that this was a Takayanagi duo gig with longtime bassist Nobuyoshi Ino until Kikuchi decided to sit in, creating some understandable friction. Agitation simmers beneath the surface adding increased tautness to the already astringent sounds. This is especially obvious on the trio selections when the guitarist’s metallic single lines become even chillier and rawer. Initially more reserved, Kikuchi’s playing soon accelerates to percussive comping, then key clangs and clips, especially on the concluding Trio II. For his part, Ino serves as a bemused second to these sound duelists, joining an authoritative walking bass line and subtly advancing swing to that final selection. On the duo tracks, he and the guitarist display extrasensory connectivity. He preserves chromatic motion with buzzing stops or the occasional cello-register arco sweep. Meanwhile with a minimum of notes, Takayanagi expresses singular broken chord motion or with slurred fingers interjects brief quotes from forgotten pop tunes. On Duo II as well, Ino’s string rubs move the theme in one direction while Takayanagi challenges it with a counterclockwise pattern. Still, fascination rests in the piano-guitar challenges with Kikuchi’s keyboard motion arpeggio-rich or sometime almost funky, while Takayanagi’s converse strategies take in fluid twangs, cadenced strumming and angled flanges.

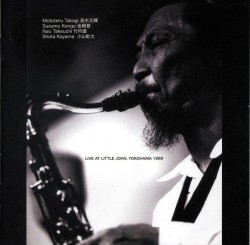

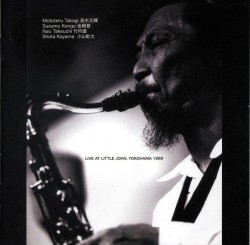

Abandoning chordal instruments and concentrating on horn textures, Live at Little John, Yokohama 1999 (NoBusiness NBCD 144 nobusinessrecords.com) provides an alternative variant of Nipponese free music. Backed only by the resourceful drumming of Shota Koyama, a trio of wind players creates almost limitless tonal variants singly, in tandem or counterpoint. Best known is tenor saxophonist Mototeru Takagi (1941-2002), who was in Takayangi’s New Direction Unit and in a duo with percussionist Sabu Toyozumi. The others who would later adopt more conventional styles are Susumu Kongo who plays alto saxophone, flute and bass clarinet, and Nao Takeuchi on tenor saxophone, flute and bass clarinet. No compromising of pure improvisation is heard on this CD’s three lengthy selections, although there are times when flute textures drift towards delicacy and away from the ratcheting peeps expelled elsewhere. Whether pitched in the lowing chalumeau register or squeaking clarion split tones, clarinet textures add to the dissonant sound mosaic. This isn’t anarchistic blowing however, since the tracks are paced with brief melodic interludes preventing the program from overheating. The more than 40 minute Yokohama Iseazaki Town gives the quartet its greatest scope, as vibrating split tones pass from one horn to another with percussion crunches keeping the exposition chromatic. Takagi’s hardened flutters and yowling vibrations may make the greatest impression, but Kongo’s alto saxophone bites are emphasized as well. Although space exists for clarion clarinet puffs and transverse flute trilling, it’s the largest horn’s foghorn honks and tongue-slaps that prevent any extraneous prettiness seeping into the duets. Still, with canny use of counterpoint and careful layering of horn tones backed by sprawling drum raps, the feeling of control is always maintained along with the confirmation of how the balancing act between expression and connection is maintained.

Abandoning chordal instruments and concentrating on horn textures, Live at Little John, Yokohama 1999 (NoBusiness NBCD 144 nobusinessrecords.com) provides an alternative variant of Nipponese free music. Backed only by the resourceful drumming of Shota Koyama, a trio of wind players creates almost limitless tonal variants singly, in tandem or counterpoint. Best known is tenor saxophonist Mototeru Takagi (1941-2002), who was in Takayangi’s New Direction Unit and in a duo with percussionist Sabu Toyozumi. The others who would later adopt more conventional styles are Susumu Kongo who plays alto saxophone, flute and bass clarinet, and Nao Takeuchi on tenor saxophone, flute and bass clarinet. No compromising of pure improvisation is heard on this CD’s three lengthy selections, although there are times when flute textures drift towards delicacy and away from the ratcheting peeps expelled elsewhere. Whether pitched in the lowing chalumeau register or squeaking clarion split tones, clarinet textures add to the dissonant sound mosaic. This isn’t anarchistic blowing however, since the tracks are paced with brief melodic interludes preventing the program from overheating. The more than 40 minute Yokohama Iseazaki Town gives the quartet its greatest scope, as vibrating split tones pass from one horn to another with percussion crunches keeping the exposition chromatic. Takagi’s hardened flutters and yowling vibrations may make the greatest impression, but Kongo’s alto saxophone bites are emphasized as well. Although space exists for clarion clarinet puffs and transverse flute trilling, it’s the largest horn’s foghorn honks and tongue-slaps that prevent any extraneous prettiness seeping into the duets. Still, with canny use of counterpoint and careful layering of horn tones backed by sprawling drum raps, the feeling of control is always maintained along with the confirmation of how the balancing act between expression and connection is maintained.

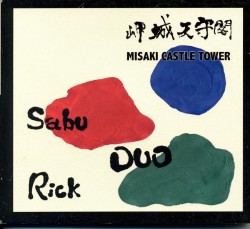

Takagi’s former duo partner, percussionist Sabu Toyozumi (b.1943) continues playing free music as he has since the mid-1960s. Recently he’s formed a partnership with American alto saxophonist Rick Countryman, with Misaki Castle Tower (Chap Chap Records CPCD-0190 chapchap-music.com) the most recent session. It’s fitting that one track is entitled Ode to Kaoru Abe since the saxophonist who overdosed at 29 in 1978 is a Charlie Parker-like free jazz avatar in Japan. While the healthy duo’s homage is strictly musical, Countryman’s spiralling tones, modulated squeaks and brittle reed interjections are aptly seconded by Toyozumi’s hard ruffs and cymbal pops. Segues into shaking flattement, renal snarls and multiphonics characterize the saxophonist’s playing on other tracks and the drummer responds with positioned nerve beats, complementary rim shots and restrained press rolls. Hushed tone elaborations, during which Countryman moves pitch upwards with every subsequent breath, distinguish the concluding Myths of Modernization from the preceding tracks. But the saxophonist’s ability to snake between clarion peeps and muddy smears when not eviscerating horn textures, remains. The summation comes on that track, as articulated reed squeezes and stops meet irregular drum bops and ruffs.

Takagi’s former duo partner, percussionist Sabu Toyozumi (b.1943) continues playing free music as he has since the mid-1960s. Recently he’s formed a partnership with American alto saxophonist Rick Countryman, with Misaki Castle Tower (Chap Chap Records CPCD-0190 chapchap-music.com) the most recent session. It’s fitting that one track is entitled Ode to Kaoru Abe since the saxophonist who overdosed at 29 in 1978 is a Charlie Parker-like free jazz avatar in Japan. While the healthy duo’s homage is strictly musical, Countryman’s spiralling tones, modulated squeaks and brittle reed interjections are aptly seconded by Toyozumi’s hard ruffs and cymbal pops. Segues into shaking flattement, renal snarls and multiphonics characterize the saxophonist’s playing on other tracks and the drummer responds with positioned nerve beats, complementary rim shots and restrained press rolls. Hushed tone elaborations, during which Countryman moves pitch upwards with every subsequent breath, distinguish the concluding Myths of Modernization from the preceding tracks. But the saxophonist’s ability to snake between clarion peeps and muddy smears when not eviscerating horn textures, remains. The summation comes on that track, as articulated reed squeezes and stops meet irregular drum bops and ruffs.

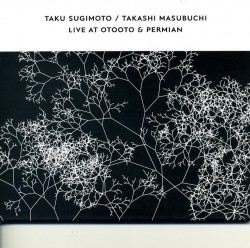

Although they play the same instrument as Takayanagi, the sounds from Taku Sugimoto (electric guitar) and Takashi Masubuchi (acoustic guitar) on Live at Otooto & Permian (Confront Core Series core 16 confrontrecordings.com/core-series) reflects a new minimalist genre of Japanese improvisation. Called Onkyo, which loosely translates as quiet noise, it’s as introspective as free jazz is brash. Through a sophisticated use of voltage drones, string percussion and harmonic transformation, these two guitarists prevent the five selections recorded at two Tokyo clubs from being bloodless. With the electric guitar projecting a buzzing undercurrent, harsh jabs, bottleneck-like twangs and inverted strums inject rhythmic and harmonic transformation into the tracks even as the narratives unroll horizontally. While the gradual evolution is rigid, there are sequences as on At Permian II, where repetitive undulations from both join singular cells into a distant melody. Plus, by moving patterns between guitarists, the duo ensures that neither droning continuum nor singular string prods predominate, making sound transformation as logical as it is unforced.

Although they play the same instrument as Takayanagi, the sounds from Taku Sugimoto (electric guitar) and Takashi Masubuchi (acoustic guitar) on Live at Otooto & Permian (Confront Core Series core 16 confrontrecordings.com/core-series) reflects a new minimalist genre of Japanese improvisation. Called Onkyo, which loosely translates as quiet noise, it’s as introspective as free jazz is brash. Through a sophisticated use of voltage drones, string percussion and harmonic transformation, these two guitarists prevent the five selections recorded at two Tokyo clubs from being bloodless. With the electric guitar projecting a buzzing undercurrent, harsh jabs, bottleneck-like twangs and inverted strums inject rhythmic and harmonic transformation into the tracks even as the narratives unroll horizontally. While the gradual evolution is rigid, there are sequences as on At Permian II, where repetitive undulations from both join singular cells into a distant melody. Plus, by moving patterns between guitarists, the duo ensures that neither droning continuum nor singular string prods predominate, making sound transformation as logical as it is unforced.

Too often Western listeners think of unconventional Japanese music as foreign, frightening and impenetrable. As these sessions show there’s actually much to explore and appreciate with close listening.

Code of Being

Code of Being